Opening the Doors of Compassion: Cultivating a Merciful Heart

by Fr. John D. Jones

As Orthodox Christians, we recognize the ultimate goal of the Christian life to be theosis or divinization—becoming like God as much as is possible for human beings. Yet this process of theosis is not a matter of a discarnate spirituality that retreats from human need and suffering. The journey towards theosis is rather expressed through concrete acts of love and mercy in imitation of God, who is love. As St. Gregory the Theologian writes, ‘Prove yourself a god to the unfortunate by imitating the mercy of God. There is nothing so godly in human beings as to do good works.’…[doing so] constitutes a sacred obligation for us to minister in Christ’s name to our neighbor; that is, to every person in need whom we encounter (cf. Luke 10:25–37). —Metropolitan Anthony (Gergiannakis)

“Prove yourself a god to the unfortunate by imitating the mercy of God. There is nothing so godly in human beings as to do good works.” So wrote St. Greogry the Theologian near the end of his Oration XIV, On the Love of the Poor. This theme is basic to the oration from the start:

St. Elizabeth the New MartyrBeautiful is contemplation (theoria=the knowledge and vision) of God, as likewise beautiful is action (praxis). The one is beautiful because it conducts our mind upward to what is akin to it. The other is beautiful because it welcomes Christ, serves him, and confirms the power of love through good works (sec. 4)…. Of all things, nothing so serves God as mercy because nothing else is more proper to God (sec. 5)…. We must, then, open our hearts to all the poor [and] those in distress from whatever cause (sec. 6).

But why, someone might ask, this stress on good works? Aren’t we saved by faith alone? Are good works really necessary for salvation? In the Orthodox tradition, salvation is a process of being healed from everything that estranges us from God and from one another. It is a process of growing in the communion and fellowship with the Trinity and one another for which God created us. It culminates in the gift of eternal life with God. None of us, individually or collectively, can save ourselves. Only Christ’s incarnation, death, resurrection, and the gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost can save us. Indeed, just as we sing near the end of the Divine Liturgy: “We have found the true faith, worshipping the undivided Trinity who has saved us.”

While Christ’s victory “over death and sin…is indeed complete and definitive…. [Our] personal participation in that victory is as yet far from complete” (Metropolitan Kallistos). Created with free will, God cannot compel us to love Him. God won’t drag us into eternal life with Him. We have to freely consent to the gift of life which he offers us. Our faith in Christ, and thus the Trinity, is our consent to and acceptance of the gift of Christ Himself. But faith by itself does not save us.

Certainly, we only know and experience the Trinity through faith. But “faith by itself is dead if it does not have works” (James 2:17). When faith is active with works, it is perfected by those works (James 2:22). Indeed, St. James writes that we are justified or made righteous by works and not just by faith (James 2:24), that is, a faith that is not active with works. Blessed Theophylact develops this idea:

Many are God–fearing, but fail to do the will of God. One must fear God and do His will. Both faith and works are necessary…or, to express it in the most exalted terms, divine vision (theoria) and active virtue (praxis). Faith truly comes alive only when accompanied by God–pleasing deeds.… Likewise, works are enlivened by faith. Apart from one another, both are dead.

But what sort of works? In one sense, any action that conforms to God’s will is a good work: e.g., telling the truth to someone, worshipping God with reverence, etc. In a narrower sense, good works are often identified with giving alms or money to someone in need or to some charity. But alms in this sense narrowly translates a Greek word that literally means “a work of mercy.” God, after all, does not give alms of money to people but God “performs works of mercy and executes judgment for those who are treated unjustly” (Ps. 102:6). These works include giving food to the hungry, setting the prisoners free, giving wisdom to the blind, lifting up those who are bowed down, watching over the sojourners, and upholding the widow and the fatherless (Ps. 145:7–9).

Works of mercy comprise all our actions to assist those who are in need and distress, whether spiritual, mental, or physical. They include counseling people in spiritual distress; comforting people who are grieving; feeding, clothing, and providing medical help to people in physical need or illness; even simply providing a cup of water if we don’t have money or other resources. Works of mercy can and should extend to efforts to change social structures and policies on behalf of, as well as to advocate for, those who are poor, vulnerable, or treated unjustly. Our works of mercy should express the holistic view of the Orthodox ideal that, as Archbishop Anastasios writes, “embraces everything, life in its entirety, in all its dimensions and meanings…[and seeks] to change all things for the better,” that is, the transformation of all things in a life in Christ. Works of mercy also can be performed by the collective actions of Christian communities: cathedrals, parishes, monasteries, lay associations, etc. Christian communities have been performing such works since the very beginning of the Church.

The Holy Martyrs of Paris:SS. Maria, Priest Dimitri, Ilya, and Yuri

Opening the Doors of Compassion: We Christians should consciously perform works of mercy to imitate Christ and reflect His presence within us. Our intentions and our moral character—the kind of person we are—make all the difference in doing good works for the sake of Christ. It’s a great thing to work at a homeless shelter. But if I do so simply to gain praise or recognition from others or to get someone off my back about helping at the shelter, then I am acting out of selfishness and not out of a love for Christ or for my neighbor. What sort of character should we have? What kind of person should we be or become so that our good works imitate Christ and reflect His presence within us?

“God is love” (I John 4:8). Time and again in Scripture, in our hymns, and in the writings of the church fathers and mothers, God’s love means that God is merciful and compassionate. Recall from St. Gregory that “nothing else is more proper to God” than being merciful and, we can add, being moved with compassion. Compassion is not simply a feeling. Compassion is quite different from pity, from feeling sorry for others, or even feeling empathy for others. We can have all of these feelings and remain unmoved to connect with others or do anything for them. We can feel pity for people and feel quite superior to them.

The Greek verb splanchnizomai, found in the New Testament only in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, is all too often translated as if it indicates the kinds of feelings I just mentioned rather than compassion. Sometimes it describes Jesus’ response to others, and at other times, Jesus uses the term in certain parables. But it is best translated in English as “being moved with compassion.” Compassion means “to suffer with another,” “to share the suffering of the other, to take it upon oneself” (Fr. Boris Bobrinskoy). Compassion moves us away from ourselves towards others. It expresses itself in actions for others and on their behalf. In the gospels, being moved with compassion always expresses itself in action.

Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:20–22): When the father sees his returning prodigal son at a distance, he is moved with compassion and rushes out to him (v.20). He embraces him and welcomes him back home as his son and not merely his servant. This father is one of Jesus’ images of Our Heavenly Father, “who so loved the world that he gave His only begotten Son” (John 3:16). “The Father,” writes Boris Bobrinskoy, “[is] not insensitive in the face of the passion, the suffering, and the decay of humanity,” but moved with compassion, “He sends His Son into the world He so loved.”

Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29–37): Moved with compassion, the Good Samaritan comes to the place where a Jew, typically despised by Samaritans, has been beaten and left. And he acts: “beholding him,” the Samaritan “came to him and bandaged up his wounds … and he put him on his own animal…” (v.34). Jesus tells this parable to a lawyer who tested him with the question “Who is my neighbor?” At the end of the parable Jesus does not tell him who his neighbor is. Rather, Jesus asks the lawyer a question: “Which of these three men”—the Priest, the Levite, or the Samaritan—“was a neighbor to the man fell among the robbers?” The lawyer gets the point of the parable, for he says the Samaritan “who showed mercy” is the one who was a neighbor. Jesus’ point is that if you know how to be a neighbor, you won’t wonder who your neighbor is. True neighbors draw near to others with a God–like compassion and mercy that extends to everyone.

Our icons for this parable always represent the Good Samaritan by Christ. Origen identifies Christ, the Good Samaritan, as our neighbor. St. Clement of Alexandria elsewhere adds: “We call the savior our neighbor because he drew near to us in saving us.” And Blessed Theophlyact develops this idea: “Our Lord and God…journeyed to us…. He did not just catch a glimpse of us as He happened to pass by. He actually came to us and lived together with us and spoke to us. Therefore, He at once bound up our wounds.”

Being moved with compassion involves being attuned to others. The compassionate person, like our compassionate God, takes notice of others and is attuned to whether they are in distress from whatever cause and regardless of who they are. For St. John Chrysostom, compassionate attunement “is most especially characteristic of the saints. Not glory, nor honor, nor anything else is more precious to them than their neighbor’s welfare and salvation.” Compassionate people, in imitating God Himself, are moved to interact with others, to bear their burdens and sufferings with them, and to alleviate them as possible.

Several texts in Matthew, Mark, and Luke indicate that Jesus was moved by compassion. In every case, Jesus’ compassion leads Him to act or do a good work, a work of mercy. Here are some examples:

Moved with compassion, our Lord takes note that the crowds who have listened to Him are hungry and that it is late in the day. Our Lord then takes action to feed them (Mark 8:1–8, cf. Matt. 14:14ff.).

Moved with compassion, Jesus acts to heal two blind men by touching their eyes and restoring their sight (Matt. 20:33–34).

Moved with compassion for the widowed mother who has just lost her only son, Jesus stops the funeral procession and restores the son to life (Luke 7:11–16).

Moved with compassion for the multitude “because they were … like sheep having no shepherd,” He then acts by commissioning the disciples to go to the lost sheep of Israel: “And as you go,” Jesus tells them, “preach, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand.’ Heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse the lepers, cast out demons” (Matt 9:34–37, 10:7–8, cf. Mark 6:34–44).

The Parable of the Unforgiving Servant (Matt. 18:23–35) or, what the kingdom of heaven is like: Moved with compassion, a king forgives his servant who owes him a ridiculously large sum of money. The king releases him from debtor’s prison. But when this servant won’t forgive a fellow servant a small debt, he shows he doesn’t really understand the king’s action.

The servant rejects the sort of “economy” found in the kingdom of heaven. This economy is not a market economy in which we are encouraged to make as much money as we can for ourselves. It is not a barter economy in which we trade with others who can give us something in return. It is not a tit–for–tat or you–scratch–my– back–and–I’ll–scratch–your–back economy. It is not an economy in which we do business only with those dear to us or who can do something for us.

The economy in the kingdom of heaven is a gift economy in which we are all invited to participate. When he compassionately forgave the debts of the servant, the king gave a gift of forgiveness and compassion to the servant. The servant, however, did not pass that gift on by forgiving his fellow servant. He wasted both the compassion and forgiveness given to him. So, he excluded himself from the kingdom of heaven. As Blessed Theophlyact writes:

The person who lacks compassion is not the one who remains in God, but the one who departs from God and is a stranger to Him…The master in His love for humankind takes issue with the [unmerciful] servant in order to show that it is not the master, but the savagery and the ingratitude of the servant, that has revoked the gift.

The fundamental economic principle, if you will, in the kingdom of heaven is “freely you have received, freely give” (Matt. 10:8). We freely receive the great gift of Christ Himself and His love for us in and through the Holy Spirit. What are we to do with this love? As Christ tells us, “Love one another as I have loved you” (John 13:34). In passing Christ’s love for us to others, we return that love to Christ. That is what it means to do good works for the sake of Christ.

St. Herman of AlaskaGod’s love for the world is an ecstatic, energetic outpouring of Himself to the world. If we freely accept this gift, e.g., the Eucharistic gifts of the Body and Blood of our Lord, in true faith, what else should we do but join our love to Him and transmit His love to others? This is why faith in God, the Trinity, must express itself in actions. “Faith without works is dead” since such faith amounts to refusing the gift of love, who is Christ, and the Trinity. Faith without compassionate and merciful good works amounts to saying “Thanks, but no thanks” to God Himself and His love and mercy.

Cultivating a Merciful Heart: St. Gregory the Theologian delivered his Oration On the Love of the Poor at a time when leprosy was a major illness. He hammers away at the utterly inhumane neglect and rejection that many Christians of his day showed to lepers. Lepers were often driven from cities, abandoned, denigrated as sub–human, and left to suffer in poverty and terrible pain because many people simply could not stand to be around them and thought they were cursed by God. In our modern societies, people with mental illnesses, serious physical deformities, people with AIDS, prisoners, the poor, immigrants, indigenous people, unborn children and others all too often have been treated like lepers.

If we are moved with a Christ–like compassion for others, then we will be moved to serve all others without any exception—even our enemies—because we affirm and experience all others as brothers and sisters in Christ who bear the image of Christ within them. Our Lord, after all, associated with all of the despised people of his time: prostitutes, tax collectors, lepers, the poor, Samaritans, etc. The Good Samaritan exemplified a Christ–like compassion when he rendered assistance to a Jew, for he broke down all of the common psychological and social barriers between Samaritans and Jews.

Serving and praying for others with compassion is not always easy, and not just because we may be unclear about how to respond to others with compassion.For instead of opening our hearts to others, we often close and harden our hearts, and push others away from us. Think of a time when you’ve been very angry with someone. Think of how your chest tightens, how your mind is filled with animosity towards that person, and how you push him or her away from you. So too, there are many homeless people in our cities. It’s not always pleasant to draw near to them (that is, be neighborly to them) especially if their behavior reflects a significant mental illness such as schizophrenia. They are, however, rarely if ever a danger to anyone. And yet when we see homeless persons, it’s very easy physically and psychologically to recoil from them and avoid them. If we harden our hearts to others in these ways, how can we be moved by compassion to serve them as our brothers and sisters in Christ? What are we to do with our hearts when they all too often become hardened to others and, at the same time, to Christ?

In the Orthodox Christian spiritual life, our hearts are the spiritual center of our existence. Our heart is not a place filled with mere sentimental emotions. It is the place in which each of us—body, soul, mind, and spirit—is able to stand in God’s presence. The heart, as Metropolitan Kallistos writes, is “the center of the person, the seat of wisdom…the meeting place between the Divine and the human…the place of divine indwelling, where…God is at work within me.” But the heart is also the place of all kinds of passions and thoughts that will close off this meeting place between ourselves and God if we yield to them.

We engage in prayer, fasting, repentance, and confession, and we participate in the mysteries or sacramental life of the Church to clear away the thoughts and passions that shut us up within ourselves. To nurture and protect the love and compassion which God bestows upon us, we must cooperate with the Holy Spirit to cultivate a merciful and pure heart, a heart overflowing with the love of God the Father in and through the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the communion of the Holy Spirit (2 Cor. 13:14, which is used as the blessing at the beginning of the Anaphora of the Divine Liturgy).

One traditional way of cultivating a merciful heart is through the frequent repetition of the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” We do not repeat this prayer to lull ourselves into a meditative state. We do not repeat this prayer primarily for relief from some particular struggle which we are enduring. We repeat this prayer—which is based on the prayer of the Publican—to stand before God fully attentive to all of the ways in which we betray our love for Him and others, thereby pushing Him and them away from us.

The martyrs and saints were extremely conscious of how often their love and faith faltered. They knew—they experienced—that while God’s love for us never fails (Matt. 28:20, Rom 8:39), our love for God and for each other all too often does fail. They knew with great honesty and humility that we are too easily led astray by the passions and selfish desires that harden our hearts and close us off to God and to one another. The saints and martyrs constantly sought Christ’s mercy and forgiveness. If I am honest with myself—“No matter how often I repent, I appear a liar before God, and repent with trembling” (Compline Prayer to the Theotokos)—as the first among sinners, I become aware of my constant need for God’s mercy and forgiveness.

We do not, however, repeat the Jesus prayer to beat ourselves up with guilt and get stuck in our past. Rather, the deep awareness of our sinfulness should make us aware of our utter dependence upon God’s life and healing love. Our repetition of the Jesus prayer can make us aware that God’s healing love and forgiveness are an utterly merciful gift. Nothing we do, say, or believe merits this mercy. The message of Christ’s forgiveness is always a message of encouragement and healing: You’ve stumbled and faltered; ok, pick yourself up. “Arise, take up your bed and walk” (Mark 2:9, John 5:8), and get back to the business of forging a life grounded in faith, love, and mercy.

If our experience of God’s mercy penetrates our hearts and minds, if we become utterly humble before God, then the grace of the Holy Spirit can cultivate a merciful heart within us. The person with such a heart is enabled to become—better: is moved to be—merciful and compassionate to others. She bears their suffering and distress, and prays and acts for the relief of that suffering and distress. The person with a merciful heart bears the crosses that come with loving others. Here is St. Isaac the Syrian’s wonderful description of the person with a merciful heart:

And what is a merciful heart? It is the heart’s burning for the sake of the entire creation, for humans, for birds, for animals, for demons, and for every created thing….From the strong and vehement mercy which grips his heart and from his great compassion, his heart is humbled and he cannot bear to hear or see any injury or slight sorrow in creation.

We can only cultivate a merciful heart and open the doors of compassion to others through the uncreated grace, life, and energy of the Holy Spirit. The great gift we receive from living with a merciful heart is that we are enabled to radiate the love of the Trinity to the world and to bring Christ to others. In doing so, we participate in the process of our salvation, of sharing in the life, love, and energy of the Holy Trinity. Our life in Christ is inseparable from our communion and fellowship with the Trinity and with one another. We cannot, after all, say we love God if we don’t love our neighbor (I John 4:20).

Put simply, in manifesting Christ’s love in the world, we grow in likeness to Christ, and, thus, the Trinity for which we were created. This is what it means to be a living icon of God. The icon of the Theotokos of the Sign often graces the apse in many ortho-dox churches. In her purity of heart at the Annunciation, she freely consents to the incarnation of our Lord within her. She bears the Son of God in the flesh. That’s why we call her “Theotokos.” Consider too the wonderful way in which we refer to the martyrs and saints: “our ven-erable and god–bearing (theophoros) fathers and mothers.”

A living icon of God is a bit like a wind spinner. The wind blows; the spinner turns and passes the wind on. A well–made spinner doesn’t try to hold onto the wind or hoard it. While wind spinners blow in response to any sort of breeze, we have to be far more vigilant about the breezes to which we respond. There is the breeze of the Holy Spirit which blows us into the gift–economy of the kingdom of heaven. It enables us to love the Lord our God with all our hearts and minds, and to love our neighbors as ourselves. There are, however, the many breezes of our own passions and thoughts as well as the seductive influences of our society. These breezes blow us away from God and our neighbors into the prideful individualism of seeking our own self–interest above everything else. The breeze of the Holy Spirit blows us in the direction of life; the other breezes, in the direction of death.

The Liturgy after the Liturgy: During the Divine Liturgy, setting “aside all earthly cares,” and drawing “near in faith and love and in the fear of God,” “we…receive the King of all invisibly upborne by the angelic hosts.” Immediately after the Divine Liturgy, we pray with St. Symeon Metaphrastes:

Freely You have given me Your Body for my food, You who are a fire consuming the unworthy. Consume me not, O my Creator, but instead enter into my members, my veins, my heart.… Cleanse me, purify me, and adorn me…. Give me understanding and illumination… Show me to be a temple of Your One Spirit and not the home of many sins.

When we return to all of our earthly cares, how can we bear the gift of the Divine Liturgy in the world? What should our liturgy after the Liturgy involve?

The Liturgy has to be continued in personal, everyday situations. Each of the faithful is called upon to continue a personal liturgy on the secret altar of his own heart, to realize a living proclamation of the good news “for the sake of the whole world.” Without this continuation, the Liturgy remains incomplete…. The sacrifice of the Eucharist must be extended in personal sacrifices for the people in need, the brothers [and sisters] for whom Christ died…. the continuation of Liturgy in life means a continuous liberation from the powers of the evil that are working inside us, a continual reorientation and openness to insights and efforts aimed at liberating human persons from all demonic structures of injustice, exploitation, agony, loneliness, and at creating real communion of persons in love (Archbishop Anastasios).

St. John Chryostom also emphasizes the Eucharistic character of our works of mercy on the altar that “is composed of the very members of Christ, and the body of the Lord becomes an altar. That altar is more venerable even than the one [in the sanctuary] which we now use. For it is holy because it is itself Christ’s Body [which] you may see lying everywhere [among the poor], in the alleys and in the market places, and you may sacrifice upon it anytime.”

St Theodosius the CenobiarchIndeed, for St. Maximus the Confessor, “the person, who can do good and does it, is truly God by grace and participation, because he has taken on a proper imitation of the energy…of His own kindness.” This is exactly what St. Gregory the Theologian wrote: “Nothing is more Godly in humans than to do good works” since the more literal translation of that text is: “There is no better way for a person to possess God than to do what is good.”

All Christians are called to preach the Gospel, the Word of God, to the world. But we should never underestimate the powerful ways in which our works of mercy can proclaim the Word of God and bring Him, Christ, to others. As a young man and a pagan, St. Pachomius was a conscript in the Roman army. Confined to a prison while awaiting service, groups of Christians came and ministered to him and the other conscripts. Wondering why they did this, he was told that Christians are “merciful to everyone including strangers.” “Pachomius, the pagan, was moved by the charity of these Christians. It remained with him all his life; for him, a Christian does good to everyone.”

Lamenting the low level of social ministry by the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow, Patriarch Alexis II wrote:

We all know that the Church is built not only by faith and by the preaching of the Word of God, but also by concrete works, without which faith is dead (James 2:18)…. An Athonite elder recently said that the world is tired of speeches. We now need not words but actions that bear witness to faith and mercy. These actions must be a sermon without words that are much more effective and convincing.

Finally: St. Theodosius the Cenobiarch was well known for his great mercy and compassion to the poor, to those who were ill and dying, and many others. St. Symeon Metaphrastes commended St. Theodosius as “the eyes of the blind, the feet of the lame, the clothes of the naked, the roof of the homeless, the physician of the sick…” And so it can be for each of us—as individuals and as Christian communities— according to the grace and unique gifts we receive from the Holy Spirit; our strengths, weakness, and circumstances; and, above all, our willingness freely to accept and to pass on to others the gift of Christ’s love for us.

We offer prayers to the Theotokos to open the doors of her compassion to us. Let us also fervently pray that she helps us open the doors of our compassion to others and animate our lives with the good works that flow from a merciful heart. Let us be moved with compassion to serve Christ by serving others. Let us be especially attuned to the poor and to all of those in distress whoever they are and for whatever reason. Let us, then, work with the grace of the Holy Spirit to be perfected as living icons of Christ and to join “the cloud of witnesses” (Heb. 12:1)—“our venerable and God–bearing fathers and mothers”—who through their faith, love, and good works bore Christ’s love—the Trinity’s love—in the world.

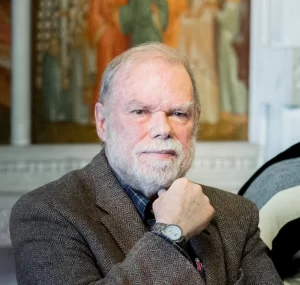

Priest John D. Jones is Professor{Anchor:_GoBack}, Department of Philosophy, Marquette University and Associate Priest at Saints Cyril & Methodius Orthodox Church (OCA) in Milwaukee. This paper is a revised version of a lecture presented at the Orthodox Christian Women’s Association Conference, Doing Good Deeds, in October 2011. A copy of the paper with notes can be obtained by emailing Fr. John at [email protected].