Death has Died, War is Over!

August 15 we celebrate the Dormition of the Theotokos, the falling asleep of Mary. August 15 is also the anniversary of the end of the Arab-Byzantine wars, by a miracle of the Theotokos.

For centuries, the Romans faced instability on their eastern front. The longest conflict in history is the series of Roman-Persian wars, which began 50 years before the birth of Christ. These wars ended in the 7th century when the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates conquered the Sassanid Empire. This did not bring peace to the Byzantine Empire, however, for these new Empires began their own expansionist campaign known as the Arab Conquests. This campaign culminated in the siege of Constantinople in 718.

The Byzantines were a notoriously peace-loving people, and viewed with derision by their contemporaries for this. They preferred to avoid open battle, often refused to fight offensively, and went to great lengths to achieve diplomatic solutions, even if it meant paying hefty tributes. As such, when the siege began, the Byzantine Emperor offered a gold ransom for every single person in the city if the siege were called off. Unfortunately the Umayyads refused.

What followed was a grim thirteen moth siege. Unfavorable winds hindered the Umayyad navy, while a harsh winter overwhelmed the troops. On August 15, 718, the Umayyads decided the siege was a failure and withdrew. Reportedly, a great storm and volcanic activity hindered the retreat of the invaders.

Inside the city that day, the faithful had gathered in the churches to celebrate the Feast of the Dormition, the falling asleep of the Theotokos. The people of Constantinople attributed the peace that had broken out to Mary, and began commemorating the day as a 'miracle'. They did not attribute the peace to their soldiers or their defensive capabilities. Rather, they saw in the decision of the Umayyads to withdraw the intervention of the Queen of Peace, who softens the heart of those who have grown violent.

In the aftermath, peace and stability was established on the eastern front for the first time in 9 centuries. Historians attribute this to the events of August 15, 718. The Byzantines refused to take advantage of the weakened state of the Umayyad forces following the siege. Had they done so, they could have conquered much of the Arab territory, and may have sown the seeds for another few centuries of conflict. Instead, they sought to win peace and security. Aside from scattered instances of banditry, the frontier did not experience any major war again until the thirteenth century with the beginning of the Ottoman-Byzantine conflict. The Abbasid Empire replaced the Umayyad, and the Roman Byzantines sent emissaries on peace missions, establishing a robust cultural exchange and several centuries of peace. For once, in the middle of Byzantine history, war was over.

The Dormition appropriately coincides with the commemoration of this peace every year. Observance of the feast began sometime in the sixth century, just at the end of the Roman-Sassanid wars. It commemorates the death of Mary. But rather than being referred to in these terms, the phrase Dormition, or falling asleep is used. The reason for this is that the Dormition became a mirror of Christ's glorification. Christ died violently on the cross, while himself remaining nonviolent, so that death itself could be killed. Christ stormed hades so that no one else would have to languish there. Christ was glorified by the Father, gaining a resurrection body and returning to the shekinah of the Heavenly Father. Christians commemorate this with a great fast, followed by a great feast.

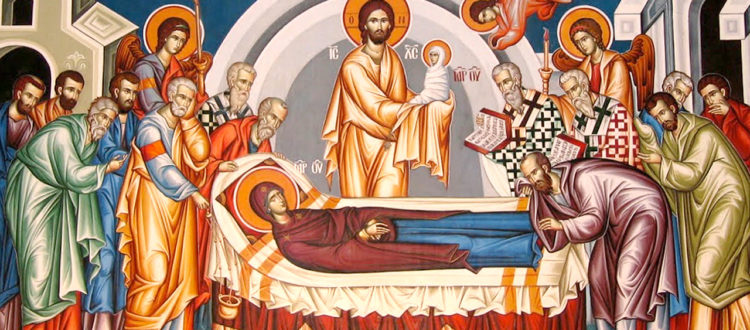

The traditions that came to be associated with the Dormition mirror this. Christians first fast for fifteen days, and then feast. Mary is commemorated as dying peacefully, and then after three days is glorified, raised from the dead and taken to the shekinah presence of God. Because Christ has been glorified and death has died, Mary does not fully die as one would have before Christ. Rather she 'falls asleep' and is then raised and glorified. Everything evokes Christ's death, but is modified. The icons of the Crucifixion and Resurrection are filled with action. The Dormition icon rests peacefully. Christ holds the infant Mary, evoking and contrasting the tumultuous birth of Christ. The reason behind this modified parallelism is that Mary comes to represent all humanity. All humans are destined not to die, but to be raised because of the raising of Christ. And with Mary we see this in the middle of history, rather than at the end.

Taken together, these two commemorations complement one another. Death has died because Christ is risen and we have seen this in this world, in the middle of history. War is over because of the victory of the Prince of Peace, and we can see this as well in the middle of history. War, death, destruction have lost. Peace is secured. This is not just an end times proclamation, but insofar as we live in Christ and honor his mother, we too can taste of these things in our own time.

As Mary herself showed us on the Feast of the Dormition in 718, there is no better icon of the death of death than the end of war.

Nicholas Sooy

editor, In Communion