Becoming the Gospel: the example of four saints

by Jim Forest

We should try to live in such a way that if the Gospels were lost, they could be re-written by looking at us.

These few words from Metropolitan Anthony Bloom were the underlying theme of all his books, lectures and sermons. To be a Christian is to devote one's life to becoming the Gospel. The Gospel exists so that each of us can make of our lives a unique living translation of its stories, sayings and parables. Like no other book in the world, it is meant to be lived, to be lived in such a way that those who have not read the text might guess at least its major themes simply by knowing those who are absorbing the text into their lives.

Orthodox ritual goes to great lengths to draw our attention to the Gospel. This small book, containing only the texts of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, is enthroned on the altar. It is something we bow toward and often kiss. Side by side with the Cross, it is before us when we confess our sins. Held high, it is solemnly carried through the church in procession every week. It is decorated with relief icons. During services, it is not simply read but chanted so that the words of the Gospel might enter us more deeply.

Only a degree less important in the life of the Orthodox Church is our close attention to the lives of the saints, that is to those people who, to a remarkable degree, in some way became the Gospel. Each saint provides a unique translation of the Gospel. Each saint not only helps us see what the Gospel is about but also how diverse are the ways in which a person can become the Gospel. Each saint throws a fresh light on how the Gospel can be lived more fully in the particular circumstances of our lives.

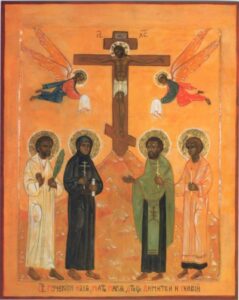

I would like to look at the example given by several people newly recognized as saints: Mother Maria Skobtsova plus three others closely associated with her: the priest Dimitri Klepinin, her friend and collaborator Ilya Fondaminsky; and Mother Maria's son, Yuri. On the first weekend of May, in the Cathedral of St. Alexander Nevsky in Paris, their names were added to the Church's calendar of saints.

Mother Maria Skobtsova was born in 1891 in Latvia -- then part of the Russian Empire -- and was given the name Elizaveta. She grew up near the Black Sea and later in St. Petersburg. Her childhood faith collapsed following her father's death, but as a young adult her faith was gradually reborn. Liza prayed and read the Gospel and the lives of saints. While regarding herself as a socialist, it seemed to her that the real need of the people was not for revolutionary theories but for Christ. She wanted "to proclaim the simple word of God," she told Alexander Blok in 1916. She was the first woman to study at the theological institute in St. Petersburg. After Lenin's forces took power, she narrowly escaped summary execution by convincing a Bolshevik sailor that she was a friend of Lenin's wife.

One of the many refugees who fled Russia during the civil war, by the time she reached Paris in 1923 she had finished one marriage and started another and was the mother of three.

One child, Nastia, died very young -- the kind of death that visited many Russian families struggling to survive in France in those days. Liza's monastic vocation is partly connected with Nastia's death in the winter of 1926. During her month-long vigil at her daughter's bedside, Liza came to feel how she had never known "the meaning of repentance."

"Now I am aghast at my own insignificance," she wrote. "I feel that my soul has meandered down back alleys all my life. And now I want an authentic and purified road. Not out of faith in life, but in order to justify, understand and accept death .... No amount of thought will ever result in any greater formulation than the three words, 'Love one another,' so long as it is love to the end and without exceptions. And then the whole of life is illumined, which is otherwise an abomination and a burden."

After Nastia's burial, Liza became aware "of a new and special, broad and all-embracing motherhood." She emerged from her mourning with a determination to seek "a more authentic and purified life." She felt she saw a "new road before me and a new meaning in life, to be a mother for all, for all who need maternal care, assistance, or protection."

In 1930, she was appointed traveling secretary of the Russian Student Christian Movement, work which put her into daily contact with impoverished Russian refugees in cities, towns and villages throughout France.

She took literally Christ's words that he was always present in the least person. She wrote:

If someone turns with his spiritual world toward the spiritual world of another person, he encounters an awesome and inspiring mystery .... He comes into contact with the true image of God in man, with the very icon of God incarnate in the world, with a reflection of the mystery of God's incarnation and divine manhood. And he needs to accept this awesome revelation of God unconditionally, to venerate the image of God in his brother. Only when he senses, perceives and understands it will yet another mystery be revealed to him -- one that will demand his most dedicated efforts .... He will perceive that the divine image is veiled, distorted and disfigured by the power of evil .... And he will want to engage in battle with the devil for the sake of the divine image.

Metropolitan Anthony, then a layman in Paris studying to become a physician, recalled a story about her from this period that he heard from a friend:

She went to the steel foundry in Creusot, where many Russian refugees were working. She came there and announced that she was preparing to give a series of lectures on Dostoevsky. She was met with general howling: "We do not need Dostoevsky. We need linen ironed, we need our rooms cleaned, we need our clothes mended -- and you bring us Dostoevsky!" And she answered: "Fine, if that is needed, let us leave Dostoevsky alone." And for several days she cleaned rooms, sewed, mended, ironed, cleaned. When she had finished doing all that, they asked her to talk about Dostoevsky. This made a big impression on me, because she did not say: "I did not come here to iron for you or clean your rooms. Can you not do that yourselves?" She responded immediately and in this way she won the hearts and minds of the people.

While her work for the Russian Student Christian Movement suited her, she began to envision a new type of community, "half monastic and half fraternal," which would connect spiritual life with service to those in need, in the process showing "that a free Church can perform miracles."

Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, dean of the St. Sergius Theological Institute and her confessor, was a source of support. He was a confessor who respected the freedom of all who sought his guidance, never demanding obedience, never manipulating. Another key figure in her life was her bishop, Metropolitan Evlogy. He was the first one to suggest to Liza the possibility of becoming a nun. Assured by him that she would be free to develop a new type of monasticism, engaged in the world and marked by the "complete absence of even the subtlest barrier which might separate the heart from the world and its wounds," in March 1932 Liza was professed as a nun, receiving the name Maria. Her goal was to create a model of what she called "monasticism in the world."

Here again there is an interesting impression by Metropolitan Anthony of what Mother Maria was like in those days:

She was a very unusual nun in her behavior and her manners. I was simply staggered when I saw her for the first time in monastic clothes. I was walking along the Boulevard Montparnasse and I saw: in front of a cafe, on the pavement, there was a table, on the table was a glass of beer and behind the glass was sitting a Russian nun in full monastic robes. I looked at her and decided that I would never go near that woman. I was young then and held extreme views.

Mother Maria's intention was "to share the life of paupers and tramps," but how she would do so was not yet clear. She knew that it could not be a life of withdrawal from the sufferings of the world. "Everyone is always faced," she wrote, "with the necessity of choosing between the comfort and warmth of an earthly home, well protected from winds and storms, and the limitless expanse of eternity, which contains only one sure and certain item ... the Cross."

With financial help and the encouragement of Metropolitan Evlogy, she started her first house of hospitality. As the building was unfurnished, the first night she wrapped herself in blankets and slept on the floor beneath the icon of the Protection of the Mother of God. Donated furniture began arriving, and also guests, mainly unemployed young Russian women. To make room for others, Mother Maria gave up her own room and instead slept on an iron bedstead in the basement. A room upstairs became a chapel while the dining room doubled as a hall for lectures and discussions.

When the first house proved too small, a new location was found -- a house of three storeys at 77 rue de Lourmel in the fifteenth arrondisement, an area where many impoverished Russian refugees had settled. While at the former address she could feed only 25, here she could feed a hundred. A stable behind the house was made into a church. The house was a modern Noah's Ark able to withstand the stormy waves the world was hurling its way. Here the guests could regain their breath "until the time comes to stand on their two feet again."

As the work evolved, she rented other buildings, one for families in need, and another for single men. A rural property became a sanatorium.

Donations were given and quickly spent, yet the community purse was never empty for long. She sometimes recalled the Russian story of the ruble that could never be spent. Each time it was used, the change given back proved to equal a ruble. It was exactly this way with love, she said: No matter how much love you give, you never have less. In fact you discover you have more -- one ruble becomes two, two becomes ten.

Mother Maria felt sustained by the opening verses of the Sermon on the Mount: "Not only do we know the Beatitudes, but at this hour, this very minute, surrounded though we are by a dismal and despairing world, we already savor the blessedness they promise."

Of course she had her critics. The house on rue de Lourmel, some charged, was an "ecclesiastical Bohemia." There should be more emphasis on services, less on hospitality. But Mother Maria's view was that "the Liturgy must be translated into life. It is why Christ came into the world and why he gave us our Liturgy."

She had an unusual opinion regarding exile. In her view, far from being a catastrophe, it was a heaven-sent opportunity to renew the Church in ways that would have met with repression in her mother country:

What obligations follow from the gift of freedom which [in our exile] we have been granted? We are beyond the reach of persecution. We can write, speak, work, open schools .... At the same time, we have been liberated from age-old traditions. We have no enormous cathedrals, [jewel] encrusted Gospel books, no monastery walls. We have lost our environment. Is this an accident? Is this some chance misfortune?... In the context of spiritual life, there is no chance, nor are there fortunate or unfortunate epochs. Rather there are signs which we must understand and paths which we must follow. Our calling is a great one, since we are called to freedom.

She saw expatriation as an opportunity "to liberate the real and authentic." It was similar to the opportunity given to the first Christians. "We must not allow Christ," she said, "to be overshadowed by any regulations, any customs, any traditions, any aesthetic considerations, or even any piety."

In September 1935 Orthodox Action was founded. The name was proposed by her friend Nicholas Berdyaev. The co-founders included the theologian Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, the historian George Fedotov, the literary scholar Constantine Mochulsky, her long-time co-worker Fedor Pianov, and Ilya Fondaminsky, the editor of various Russian expatriate journals who had once had a post in the Kerensky government. Metropolitan Evlogy was honorary president. Mother Maria was chairman. Its projects included hostels, rest homes, schools, camps, hospital work, help to the unemployed, assistance to the elderly, and publication of books and pamphlets. By now many co-workers were involved.

While many valued what she and her co-workers were doing, there were others who were scandalized with the shabby nun who was so uncompromisingly devoted to the duty of hospitality that she would leave a church service to answer the door bell. "For church circles we are too far to the left," Mother Maria noted, "while for the left we are too church-minded."

Following the departure for England of the first chaplain, Fr. Lev Gillet, in October 1939, Metropolitan Evlogy sent another priest to rue de Lourmel: Father Dimitri Klepinin, then 35 years old. He had been born in Russia in 1904. He came to Paris from Belgrade in 1925 to study at the St. Sergius Theological Institute. Like Mother Maria, he was a spiritual child of Father Sergei Bulgakov. A man of few words, great modesty and a profound love of the Liturgy, Father Dimitri proved to be a major partner in Mother Maria's work.

The last phase of the life of Mother Maria and her co-workers -- these now included her son Yuri -- was shaped by World War II and Germany's occupation of France.

Paris fell on the 14th of June 1940. France capitulated a week later. With defeat came greater poverty and hunger for many people. Local authorities in Paris declared the house at rue Lourmel an official food distribution point.

Paris was now a prison. "There is the dry clatter of iron, steel and brass," wrote Mother Maria. "Order is all." Russian refugees were among the particular targets of the occupiers. In June 1941, a thousand were arrested, among them her friend Ilya Fondaminsky. His long delayed baptism occurred within the makeshift Orthodox chapel at the prison camp in Compiegne. He died at Auschwitz the following year.

When the Nazis issued special identity cards for those of Russian origin living in France, Mother Maria and Father Dimitri refused to comply, though they were warned that those who failed to register would be regarded as citizens of the USSR -- thus enemy aliens -- and be punished accordingly.

Early in 1942, Jews began to knock on the door at rue de Lourmel asking Father Dimitri if he would issue baptismal certificates to them. The answer was always yes. The names of those supposedly baptized were duly recorded in his parish register in case there was any cross-checking by the police or Gestapo. Father Dimitri was convinced that in such a situation Christ would do the same.

In June the Jews of occupied France were ordered to wear the yellow star.

There were, of course, Christians who said that the anti-Jewish laws being imposed had nothing to do with Christians and therefore this was not a Christian problem. "There is no such thing as a Christian problem," replied Mother Maria. "Don't you realize that the battle is being waged against Christianity? If we were true Christians we would all wear the Star. The age of confessors has arrived."

In July Jews were forbidden access to nearly all public places while shopping by Jews was limited to one hour per day. A week later, there was a mass arrest. Nearly 13,000 Jews, two-thirds of them children, were brought to a sports stadium less than a mile from rue de Lourmel where they were held for five days before being transported to Auschwitz.

Mother Maria had often regarded her monastic robe as a God-send in aiding her work. Now her nun's robes opened the way for her to enter the stadium. Here she worked for three days trying to comfort the children and their parents, distributing what food she could bring in, and even managing to rescue a number of children by enlisting the aid of garbage collectors and smuggling them out in trash bins.

The house at rue de Lourmel was bursting with people, many of them Jews. She told Berdyaev that, if anyone came to the house searching for Jews, she would show them an icon of the Mother of God.

Father Dimitri, Mother Maria, Yuri and their co-workers set up routes of escape to the unoccupied south -- complex and dangerous work. An escaped Russian prisoner of war was also among those assisted. A local resistance group helped secure the food that was needed.

On February 8, 1943, Nazi security police entered the house Lourmel and found a letter in Yuri's pocket in which Fr. Dimitri was asked to provide a Jew with a false baptismal document. Yuri was arrested, and Fr. Dimitri the next day. Under interrogation he made no attempt to hide his beliefs. Called a "Jew lover," he responded by pointing to the cross he wore. "Do you know this Jew?" he asked. For this he was struck on the face.

Mother Maria's arrest followed. At first she was confined at the Gestapo headquarters in Paris in the same building where Yuri, Father Dimitri and their co-worker of many years, Feodor Pianov, were being held. Pianov later recalled the scene of Father Dimitri in his torn cassock being taunted as a Jew. One of the SS officers began to beat him while Yuri stood nearby weeping. Father Dimitri consoled him, reminding him that "Christ withstood greater mockery than this."

In April they were transferred to Compiegne. Mother Maria was able to have a final meeting with Yuri. Hours later, Mother Maria was sent in a sealed cattle truck to the Ravensbrück camp in Germany. In a letter Yuri sent to the community at rue de Lourmel, he said his mother told him "that I must trust in her ability to bear things and in general not to worry about her. Every day [Fr. Dimitri and I] remember her at the proskomidia ... We celebrate the Eucharist and receive communion each day."

"Thanks to our daily Eucharist," he reported in another letter, "our life here is quite transformed and to tell the honest truth, I have nothing to complain of. We live in brotherly love. Dima [Fr. Dimitri] ... is preparing me for the priesthood. God's will needs to be understood. After all, this attracted me all my life and in the end it was the only thing I was interested in, though my interest was stifled by Parisian life and the illusion that there might be 'something better' -- as if there could be anything better."

For nine months the three men remained together at Compiegne. "Without exaggeration," Pianov wrote after being liberated in 1945, "I can say that the year spent with [Father Dimitri] was a godsend. I do not regret that year.... From my experience with him, I learned to understand what enormous spiritual, psychological and moral support one man can give to others as a friend, companion and confessor."

On December 16, Yuri and Father Dimitri were deported to Buchenwald in Germany, followed several weeks later by Pianov. In January 1944, Father Dimitri and Yuri were sent to another camp, Dora, about 20 miles away. On the 6th of February, Yuri was "dispatched for treatment" -- a euphemism meaning sentenced to death. Four days later Fr. Dimitri died of pneumonia.

A final letter from Yuri made its way to rue de Lourmel: "I am absolutely calm, even somewhat proud to share mama's fate. I promise you I will bear everything with dignity. Whatever happens, sooner or later we shall all be together. I can say in all honesty that I am not afraid of anything any longer.... I ask anyone whom I have hurt in any way to forgive me. Christ be with you!"

At Ravensbrück, Mother Maria endured for two years, an achievement in part explained by her long experience of ascetic life. A fellow prisoner who survived recalls how Mother Maria she would recite passages from the New Testament: "Together we would provide a commentary on the texts and then meditate on them. Often we would conclude with Compline... This period seemed a paradise to us."

By March 1945, Mother Maria's condition was critical. On the 30th of March -- Good Friday, as it happened -- she entered into eternal life. The shellfire of the approaching Red Army could be heard in the distance.

Regarding her last day, accounts vary. According to one, she was simply one of the many selected for death that day. According to another, she took the place of a fellow prisoner, a Jew. Her friend Jacqueline Pery wrote afterward:

"It is very possible that [Mother Maria] took the place of a frantic companion. It would have been entirely in keeping with her generous life. In any case she offered herself consciously to the holocaust ... thus assisting each one of us to accept the cross .... She radiated the peace of God and communicated it to us."

Four saints, all victims of one of the ideological insanities that destroyed so many millions of people in the 20th century.

In them, we see an extraordinary example of what perhaps could be called "the sacrament of the open door."

Recently my wife asked me what is the most important thing in our house. I thought for a moment, then mentioned certain books and icons. "No," she said, "it is the front door. Everything depends on how we open the door. Everything depends on hospitality."

It was a startling thought. I'm sure all the newly canonized saints said very similar things many times. Indeed in one of her essays Mother Maria uses the term "the asceticism of the open door."

Controversial in life, Mother Maria remains a subject of contention to this day and I expect this controversy will continue even now that she has been recognized as a saint. While clearly she lived a life of heroic virtue and is among the martyrs of the twentieth century, her verbal attacks on nationalistic and tradition-bound forms of religious life still raise the blood pressure of many Orthodox Christians. St. Maria of Paris, as perhaps she will now be called, remains an indictment of any form of Christianity that seeks Christ chiefly inside church buildings.

All saints show us in certain ways what it means to become the Gospel. From such people, even if we knew nothing at all about the words of Christ, we could guess the outline of Christ's teaching simply by the example given by these dedicated followers. Each of their lives provides a translation of the Gospel into the circumstances of their vocation and time.

Jim Forest is secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship. This is a shortened version of a talk delivered at the Sourozh diocesan conference held in Oxford in May. The main source of biographical material used in this text is Fr. Serge Hackel's biography of Mother Maria, Pearl of Great Price, published in Britain by Darton Longman & Trodd and, in America, by St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.